what mythical creatures were believed to be active on midsummer’s eve?

Several mythical creatures from Bilderbuch für Kinder (picture book for children) between 1790 and 1830, by Friedrich Justin Bertuch

A legendary creature (mythical or mythological creature) is a type of fictional entity, typically a hybrid, that has non been proven and that is described in sociology (including myths and legends), but may be featured in historical accounts before modernity.

In the classical era, monstrous creatures such as the Cyclops and the Minotaur appear in heroic tales for the protagonist to destroy. Other creatures, such equally the unicorn, were claimed in accounts of natural history by diverse scholars of antiquity.[one] [2] [iii] Some legendary creatures take their origin in traditional mythology and were believed to be real creatures, for example dragons, griffins, and unicorns. Others were based on real encounters, originating in garbled accounts of travellers' tales, such as the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, which supposedly grew tethered to the world.[4]

Creatures [edit]

A variety of mythical animals appear in the art and stories of the Classical era. For example, in the Odyssey, monstrous creatures include the Cyclops, Scylla and Charybdis for the hero Odysseus to face. In other tales there appear the Medusa to be defeated by Perseus, the (human being/bull) Minotaur to exist destroyed by Theseus, and the Hydra to be killed past Heracles, while Aeneas battles with the harpies. These monsters thus accept the basic office of emphasizing the greatness of the heroes involved.[v] [six] [7]

Some classical era creatures, such as the (equus caballus/man) centaur, chimaera, Triton and the flight equus caballus, are found also in Indian art. Similarly, sphinxes announced as winged lions in Indian art and the Piasa Bird of North America.[8] [9]

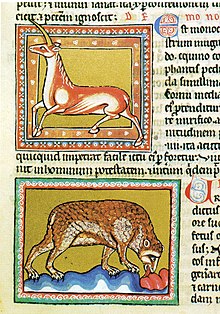

In medieval art, animals, both real and mythical, played important roles. These included decorative forms as in medieval jewellery, sometimes with their limbs intricately interlaced. Animate being forms were used to add humor or majesty to objects. In Christian art, animals carried symbolic meanings, where for instance the lamb symbolized Christ, a dove indicated the Holy Spirit, and the classical griffin represented a guardian of the expressionless. Medieval bestiaries included animals regardless of biological reality; the basilisk represented the devil, while the manticore symbolised temptation.[x]

Allegory [edit]

One function of mythical animals in the Middle Ages was apologue. Unicorns, for example, were described as extraordinarily swift and uncatchable by traditional methods.[11] : 127 It was believed that the just way for one to catch this beast was to lead a virgin to its habitation. And then, the unicorn was supposed to spring into her lap and go to sleep, at which point a hunter could finally capture it.[11] : 127 In terms of symbolism, the unicorn was a metaphor for Christ. Unicorns represented the idea of innocence and purity. In the King James Bible, Psalm 92:10 states, "My horn shalt g exalt similar the horn of an unicorn." This is because the translators of the Male monarch James erroneously translated the Hebrew word re'em as unicorn.[11] : 128 Later versions translate this as wild ox.[12] The unicorn's small size signifies the humility of Christ.[11] : 128

Another common legendary creature which served allegorical functions within the Eye Ages was the dragon. Dragons were identified with serpents, though their attributes were greatly intensified. The dragon was supposed to have been larger than all other animals.[11] : 126 It was believed that the dragon had no harmful poison but was able to slay anything information technology embraced without any demand for venom. Biblical scriptures speak of the dragon in reference to the devil, and they were used to denote sin in general during the Middle Ages.[11] : 126 Dragons were said to have dwelled in places like Ethiopia and India, based on the idea that at that place was ever heat present in these locations.[11] : 126

Concrete item was not the key focus of the artists depicting such animals, and medieval bestiaries were not conceived as biological categorizations. Creatures like the unicorn and griffin were non categorized in a separate "mythological" section in medieval bestiaries,[xiii] : 124 as the symbolic implications were of chief importance. Animals we know to have existed were yet presented with a fantastical approach. Information technology seems the religious and moral implications of animals were far more than pregnant than matching a physical likeness in these renderings. Nona C. Flores explains, "By the tenth century, artists were increasingly leap by allegorical interpretation, and abandoned naturalistic depictions."[13] : 15

Encounter also [edit]

- Non-concrete entity

- Lists of legendary creatures

- List of legendary creatures past type

- Fearsome critters

- List of cryptids

References [edit]

- ^ Phillips, Catherine Beatrice (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 581–582.

- ^ Bascom, William (1984). Alan Dundes (ed.). Sacred Narrative: Readings in the Theory of Mythology . University of California Press. p. 9. ISBN9780520051928.

table.

- ^ Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford University Printing. ISBN9780192100191 . Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Large, Mark F.; John East. Braggins (2004). Tree Ferns. Portland, Oregon: Timber Printing, Incorporated. p. 360. ISBN978-0-88192-630-ix.

- ^ Delahoyde, M.; McCartney, Katherine S. "Monsters in Classical Mythology". Washington Country University. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Grimal, Pierre. The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Blackwell Reference, 1986.

- ^ Sabin, Frances E. Classical Myths That Live Today. Silverish Burdett Company, 1940.

- ^ Murthy, K. Krishna (1985). Mythical Animals in Indian Art. Abhinav Publications. pp. 68–69. ISBN978-0-391-03287-3.

- ^ O'Flaherty, Wendy (1975). Hindu Myths: A Sourcebook. Penguin.

- ^ Boehm, Barbara Drake; Holcomb, Melanie (January 2012) [2001]. "Animals in Medieval Art". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 5 Jan 2017.

- ^ a b c d east f g Gravestock, Pamela. "Did Imaginary Animals Exist?" In The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Fine art, Life, and Literature. New York: Garland. 1999.

- ^ J. L. Schrader. The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art Bulletin, New Serial, Vol. 44, No. 1, "A Medieval Bestiary" (Summer, 1986), pp. 1+12–55, 17.

- ^ a b Flores, Nona C., "The Mirror of Nature Distorted: The Medieval Creative person'southward Dilemma in Depicting Animals". In The Medieval Globe of Nature. New York: Garland. 1993.

External links [edit]

![]() Media related to Legendary creatures at Wikimedia Eatables

Media related to Legendary creatures at Wikimedia Eatables

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legendary_creature

0 Response to "what mythical creatures were believed to be active on midsummer’s eve?"

Post a Comment